“It was a rebellion, it was an uprising, it was a civil rights disobedience.

— Stormé DeLarverie

”

BEFORE THE STONEWALL UPRISING

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, and before, it was illegal for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender Americans to live openly and freely. The FBI saved records of people known to be gay, along with the places they frequented and their friends and family. The United States Post Office kept tabs on gay citizens’ mail, gay bars and clubs were shut down, patrons of these establishments were arrested and exposed, it became illegal to wear clothes of the opposite gender, and university professors were fired if suspected to be gay.

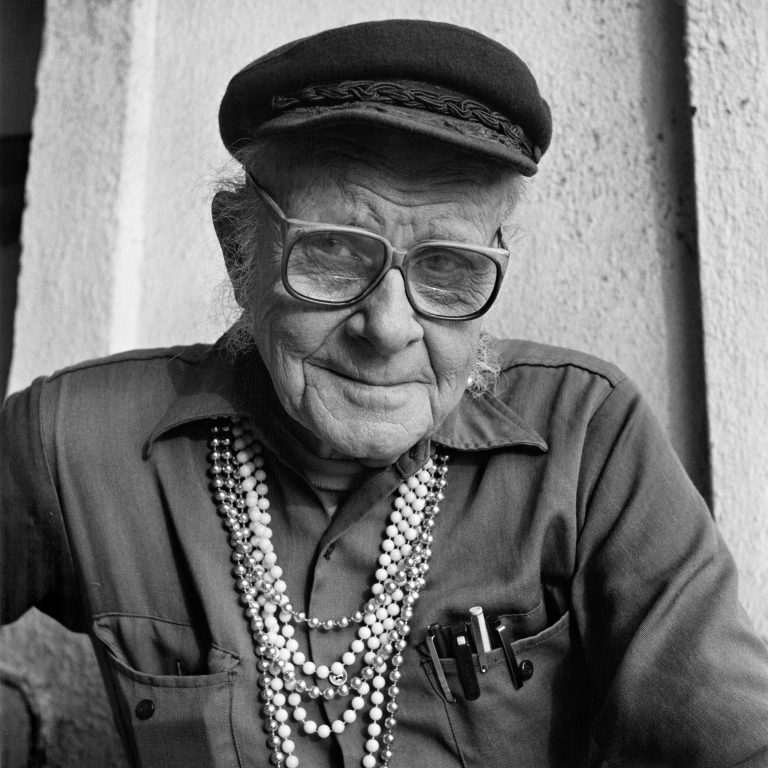

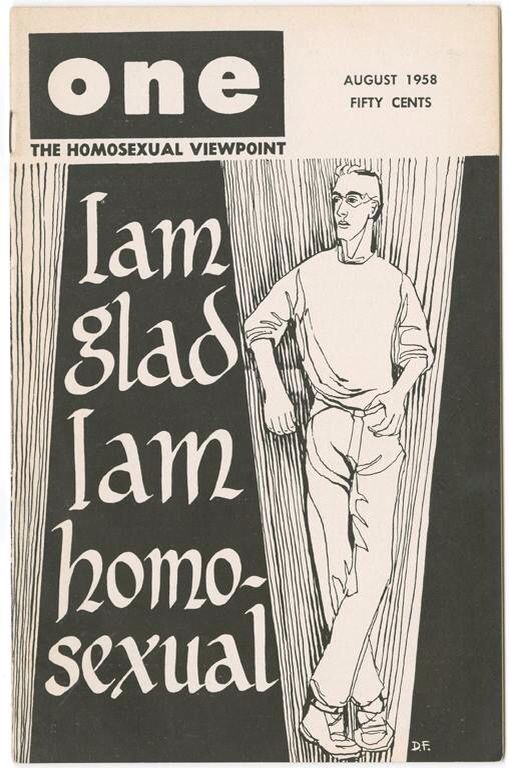

Organizations were formed to advocate for gay men and lesbians and provide them with opportunities to socialize safely and live in a society that did not accept them. Formed by Harry Hay in Los Angeles in 1951, the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis (DOB), formed by Phyllis Lyon and Del Martin in San Francisco in 1955, were two of the first national LGBTQ organizations that paved the way for future activist groups, such as the Gay Liberation Front and the Gay Activists Alliance. In 1953, One, Inc., an organization that was born from a Mattachine Society meeting, published its first monthly magazine, One, the first U.S. pro-gay publication.

THE STONEWALL INN

Gay bars and clubs were some of the few places that LGBTQ people could feel comfortable about expressing themselves. Although these bars and clubs provided people with a place of refuge relatively safe from public harassment, many of them were frequented by police harassment and raids. In 1966, the New York State Liquor Authority overturned their penalties for bars and clubs that served the LGBTQ community, but “gay behavior” was still illegal. As a result, police harassment continued and many bars continued to operate without a liquor license — one of those bars was The Stonewall Inn, which was also owned by the Mafia.

The Genovese family bribed the NYPD’s Sixth Precinct to ignore what was happening inside Stonewall so, without police oversight, they were able to cut costs on fire safety regulations, running water, clean bathrooms, and “palatable drinks.” In spite of these terrible conditions, Stonewall became one of New York’s most popular bars where gays, lesbians, drag queens, and runaways/homeless gay youths, alike, felt accepted.

Although the Mafia paid off the police, bar raids still occurred but oftentimes renegade cops would warn them, allowing time to hide the illegal alcohol — sometimes in a secret wall behind the bar or in a car down the street. Even though there had been a Stonewall raid just a few days earlier, everyone was surprised when the police came storming in at 1:20am on June 28, 1969. After being roughed up, arrested, and violated, angry Stonewall patrons and local residents who felt they could no longer tolerate the constant social discrimination and police oppression waited outside and became increasingly agitated as the events of that early morning unfolded. The crowd continued to grow as more and more people joined the masses and the frustration and rage bubbled to the surface.

When the crowd discovered that people still inside Stonewall were being beaten and violated by the police, pennies, beer bottles, and bricks started flying through the air aimed at the police and their paddy wagons. As the police were escorting a woman (who many believe was Stormé DeLarverie) out of Stonewall, she repeatedly tried to fight them off and was complaining that her handcuffs were too tight when one of the policemen hit her on the head with his baton. It was then that the woman yelled, “Why don’t you do something?!” and the crowd finally erupted in anger and began fighting against the police.

Within minutes, there were hundreds of people fighting against the police. They tried to push over the police wagons, slashed the tires, and attempted to set the bar on fire. That night, the police and riot squad were able to subdue and disperse the crowed. However, in the days that followed, the uprising continued on Christopher Street and the surrounding area with thousands of people protesting in the streets. The Stonewall Uprising was not, by any definition, the start of the LGBTQ rights movement, but it was a catalyst that awakened a new era in the fight for equal rights.

UPCOMING EVENTS

DEL TREDICI MEET UP AND POP-CONCERT AT STONEWALL

SATURDAY, MAY 11 AT 2PM | FREE

STONEWALL NATIONAL MONUMENT IN CHRISTOPHER PARK

TO LEARN MORE, CLICK HERE!

We will begin the day at the Stonewall National Monument in Christopher Park, enjoy a command performance of David Del Tredici’s Felix Variations for bass trombone featuring David’s nephew, legendary bass trombone virtuoso, Felix Del Tredici, and hear David’s reminiscences about his early life as a gay composer living and working in New York City during the 1960s.

DOGS OF DESIRE CONCERT

Featuring five new works, including Viet Cuong’s Transfiguration

SATURDAY, JUNE 1 AT 7:30PM | EMPAC CONCERT HALL

TROY, NY

Viet Cuong Program Note for Transfigured:

When something is “transfigured,” it is transformed for the better. And while there is certainly work to be done in the fight for true equality, the progress that has been made in the last five decades since the Stonewall Uprising is remarkable. In writing this piece, I watched interviews with regulars at the Stonewall Inn in the late 60s, and what struck me most was how they would use humor to deal with the horrible injustices they were facing at the time. I think everyone can relate to this in one way or another — there are times where we feel that all we can do is laugh — but coping with humor only goes so far. Eventually things erupt, just as they did in 1969 in the village.

The music begins in a playful (albeit dark and disjointed) state, as if it’s shrugging off something more important at hand. It gets increasingly agitated and distorted, eventually reaching a climax where things are forced to come together and the piece is urged to reflect on itself. As you will see through Adam Weinert’s incredible choreography and visuals, togetherness is another theme of the work. In any fight for social rights, there will be differing ideas on how something should be accomplished, and it bears repeating that we’re stronger together than we are divided.